Ever since my diagnosis, I have been gradually saying farewell to life. Two years after the diagnosis my first book was published. In various interviews, I was asked about the message of my book. Hmm, shit, never thought about this. I chose a term I have often used: LIVE, GODDAMNIT! Anita Witzier asked me what the message of the second (also the last) book was going to be. Obviously: DIE, GODDAMNIT! The one cannot do without the other. I had borrowed a Zen master statement before: “The art is wanting to live and being willing to die at the same time.”

I am saying farewell to life bit by bit. A few times I already unintentionally gave some loved ones and readers the feeling it was over. Some of them said farewell and were confused when I stubbornly lived on. It surprised and confused me too. Sorry about that. Coquetting with death is distasteful.

I know how to live by now. I am still doing it to the full. And dying?

Dying is a process, passing on is a moment. Passing on is very simple, anyone can do it. Dying is a different story really. Dying is finishing, giving back before it will be ripped out of your hands, achieving peace. Yes, peace, when you do not fight anymore, but acquiesce: it is fine as it is. Religious freaks would say, if not my but Thy will be done. Dying is also a starting point: you can only really live if you are able to die properly.

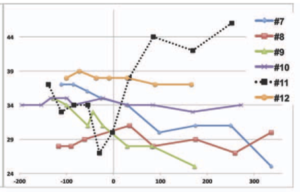

My end is approaching. It could easily be another ten years in coming, yet it is finally sinking in that the end is in sight. That is because my eyes are deteriorating, which limits my ability to communicate. Compared to last year, I barely manage to squeeze out one third of the number of letters from my eyes in one day.

I imagine I still have three boxes of a cubic metre each filled with letters at my disposal. Most of you still have a whole warehouse full left. So many, that you cannot even imagine they will ever run out. I have no idea how many letters fit in a box of a cubic metre. Many, no doubt, but not infinitely many. I do know that I will certainly need half of them in order to survive: instructing caregivers, making appointments with the doctor, et cetera. The rest of them will largely be spent on living: enjoying conversations, maintaining my social life, being useful and relevant, et cetera. If I am not careful, I will have no letters left to die: a good last will and testament, letters to Zoë, my second book, etc. I am in the fortunate position where I am allowed to die before I pass on. Suppose you are hit by a city bus with a driver who is texting, you’re not so lucky then.

It still sucks, of course, to be preoccupied with your death, no matter how happy your approach to it. Take my gravestone, for instance. Tombstones are not allowed where I will lie. A pity, because Paul had a wonderful idea for this. I discussed it with Otto, my father who, with a mischievous twinkle in his eye, came up with a trick that made it feasible. Peter, the wittiest and best goldsmith in the world, made it a reality, et voilà: a work of art! Happyhappyhappy!

Curious? Good. You will hear the real story at the funeral. Oh, shit. When I am dead. Ugh.

Now a paragraph to catch your breath and relax for a minute. There used to be a Dutch TV programme called ‘Keek op de Week’. Kees van Kooten and Wim de Bie ridiculed all of society by playing characters. They had this scene once with Kees playing himself. He arrived on a motorcycle, his motorcycle. He got off and rather timidly he explained he did not actually need that motorcycle for anything. “My wife knows, so I said it is needed for the programme. Well, hence this scene, so. I hope I will come up with something new next week.” End of scene.

I bought three different LPs of Kind of Blue. Not even different versions. All three use the same recordings from ’59. Different masterings. Iris, I need them for my blog, honestly, have a look, I am writing about them.

Oh, I wish marriage was that simple.

Zoë was sitting on my lap the other day. My breathing tube came off. I was startled, as she used to think this was scary, the noise and the disconnected tube flying in all directions. My shock proved unfounded. Sweet Zoë took the tube, fixed it onto my cannula again and said: “Here you are.”

When I was three, I nicked the car keys and started our Simca. Zoë makes better use of her talents, fortunately.

Another time, she was sitting on my lap, waiting for the bottle. She synchronised her breathing with mine. No small feat, as I breathe very fast, it is almost panting. She rubbed her cuddly toy against her nose, a typical Iris trait.

Zoë is the only two-year-old in the world who patiently waits when her daddy types a question or an answer at an exasperatingly slow pace – tick … tick …tick (not always).

I just needed these fragments, as just now I felt for the first time what it is really like to be confined. The spells during which my eyes do not work properly are growing ever longer. These are periods in which writing or conducting a conversation is impossible, such is the amount of concentration and frustration required for chiselling letters. Last year, I would type every day for twelve hours non-stop at a flying pace… Well, maybe it is just fatigue; all I do is gaze at that monitor every day. My eyes are trying to tell me I want to go out more, that they would only like to see nature for a week. I hear them, but I do not listen. Why do we knowingly do things that are bad for us?

Life and death come together in gratitude. As an emotion, gratitude gives energy, happiness, it alleviates. Gratitude as an act creates a pause, making the grateful person humble for a moment. Thanking is not selfish, perhaps the ego even briefly dies for a moment in order to create space. For what? Well, indeed for something else. No wonder why Zennies bow, Christians pray on their knees, and Muslims make themselves small on a prayer rug. Ahem. Or why you just say “Thank you” when checking out.

Life and death come together in gratitude. This is actually the reason why I started this post: gratitude. I am floating on a sea of love, carried by 10,000 hands. Really, 10,000? Well, more or less. At the end of the first book, I wrote a small word of thanks to all the professionals who participated in the strategic battle against ALS. Back then, I was able to squeeze everyone into one or two pages.

I started making a list of the people I would like to thank for their support, to conclude the second book with. Seriously, the names alone filled a whole page. If I were to elaborate … I can get away with a single line for most names. For instance: Dolf gave up his sesshin in Vught in order to do his sesshin at my place, three or four? times. Have to look up how often. For months on end, Nienke would visit every Monday morning to give me private yoga lessons, until I really wasn’t able to do this anymore. Some names I can hardly squeeze into one sentence: Daan, a nurse, selflessly facilitated a weekend trip as well as a holiday to England by travelling with me and performing the tasks of three nurses on her own, even though she practically did not know me.

It gets more difficult when you start focusing on people like Martijn or Paul or Menko. I could already pen a blog just about how our four partners made a weekend away terrifically great for me, by wiping off my tears, letting me pour my heart out, making me feel warmly welcome time and time again, or by being the only one to see how I really feel.

Doing justice to the mountains moved for us by, I will randomly mention three individuals, Trudie (private hairdresser, Daddy Days facilitator, worthy troublemaker), Pieter (It is as if Sivert wrote Into the Sea with him in mind, one line in particular) or Reneke (she followed me from New Zealand to Tarifa beach, and that was only the beginning) is next to impossible. Jiska, my other sister, by chance gave me a moment I could capture in a story, enabling me to at least capture a fraction of the support she gave me. No, even if I had a hundred boxes filled with letters: describing my gratitude in full is impossible. Occasionally, however, I try anyway.

What I intend to say, the image I want to portray, is … One of tremendous wealth. A horn of plenty of love and beautiful moments. The sea of love. I have got so much to be grateful for, it is almost obscene. My purple meditation cushion, for instance, has brought me such a great deal. Across 83 generations, Gautama Buddha first taught me how to live, and now how to survive. If you can see it, there is such an abundance of beauty, everywhere, that you will have to live on, 100%.

Once again, I am wondering: is this real? My daily life is filled with rubbish, frustration, pain, powerlessness, anger, sadness, shit. Isn’t writing about a sea of love and beauty very hypocritical? No. This sea exists, continuously, always, like the moon. I only have to look at it to see it. Sometimes I forget. Reminders of this occur in Lisanne kissing me, Juel looking at me, Miga holding me, Rembrandt coming over with Flore, Zoë existing, and I can easily go on for ten pages. They fill me, so that I can cry it out again a little later (ugh).

Nobody’s life is easy (is yours? then you are missing something), and, at times, everybody feels lonely, sad, shitty, failed. You only need to be reminded of all the beauty in your life, in order to climb back up again. Look around you, during these Christmassy merry days, and die of love.

Translation: https://uitdekunst-vertalingen.nl/vertaler-nederlands-engels/. A very good and kind translator Dutch – English.